As both an activist and a scholar, Ellen DuBois has fought for women’s equity and inclusion for over forty years. She is among the pioneers in the field of women’s history, whose groundbreaking works have expanded our understanding of the woman suffrage movement and political feminism in the 19th and 20th centuries. After completing her Ph.D. in History at Northwestern in 1975, she joined the fledging Women’s Studies program at SUNY Buffalo, where she published her first book, Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America 1848-1869 (Cornell, 1978). Her second book, Harriet Stanton Blatch and the Winning of Woman Suffrage (Yale, 1997), was awarded the Joan Kelly Memorial Prize by the American Historical Association and along with Lynn Dumenil, she authored the popular textbook Through Women’s Eyes: An American History with Documents (Bedford/St. Martin’s), currently in its 5th edition. She has also served as editor for several important collections of essays and source materials, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony: Correspondence, Writings, Speeches (Northeastern, 1992) and Unequal Sisters: A Multicultural Reader in Women’s History (with Vicki Ruiz, Routledge, 1994). Since joining the faculty of the UCLA History Department in the 1990s, she has regularly taught courses in American history, including those exploring the history of American women, gender and sexuality, as well as those tracing histories of global feminism and the civil rights movement, and, since 2012, served as a faculty affiliate of the Leve Center. She retired from UCLA as a Distinguished Professor in the Department of History and Gender Studies in 2017.

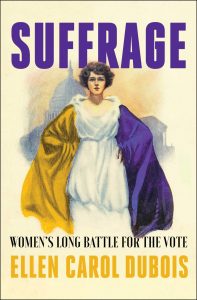

We talked with Prof. DuBois about her career as a historian and her new book, Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote (Simon and Schuster), which will be released in honor of the 100th Anniversary of the 19th Amendment in 2020.

You graduated from Wellesley in 1968, when I imagine the women’s liberation movement on campus was in full bloom. Was your engagement in feminist activism part of what drew you to the field of women’s history?

Actually, women’s liberation hadn’t really gotten started outside of New York City or Chicago in 1968. Instead I (and other soon-to-be feminists) was involved in anti-war and civil right activism. At Wellesley, although a women’s college, we worked hard on draft resistance and anti-war mobilizations. And, of course, responded to the incredible events of that year: Johnson’s announcement that he would not run again, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. Women’s liberation was not on our radar, although I do remember noting to myself that women were basically running the office of the Boston draft resistance group behind the scenes. I was deeply involved because I had a draft resister boyfriend. That’s how most of us were involved (“Girls say yes to boys who say no,” as Joan Baez said).

I gather you were active in the movement while in graduate school as well. How would you describe the relationship between feminist academics and the movement as a whole?

I actually discovered the women’s liberation movement in January 1969. A group of “WITCHES” (“Women’s International Terrorist Group from Hell”) showed up at Northwestern University where I was in my first year [of graduate school] and I was transfixed by them. As I remember, I understood and identified with their guerilla theater feminism in a Chicago second and there was no turning back from then. I think I was ready to take some sort of leadership (primed by all women’s high school and college) and also somehow recognized that these women were going to make history–I don’t mean write history, I mean make history–and I wanted to be in on it. I soon met the women who were to form the Chicago Women’s Liberation Group that fall. I formed a group at Northwestern, of graduate and undergraduate women, and we organized students on campus, putting together an informational pamphlet for women students.

Either that year or the next I began to work with my professor, Jesse Lemisch (visiting from University of Chicago), to assemble a collection of women’s history documents. No such thing yet existed. We got a small contract from Prentice Hall, which we never fulfilled. But my own work as an historian of women’s rights began there. My first article, published in 1970 in a movement journal entitled Women: A Journal of Liberation, was focused on the first historical figures that caught my attention: Sarah and Angelica Grimke. From there, I moved on to Seneca Falls and the early women’s rights movement and Elizabeth Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (to whom I have remained attached ever since). My second article, entitled “The Radicalism of the Woman Suffrage Movement,” was published in Feminist Studies. Although now a regular academic journal, at the time it was published by feminist activists with no institutional support. By the middle of my second graduate year, I was committed to writing the history of early woman suffrage, which became my first book Feminism and Suffrage, as my doctoral degree. I had two professors: Christopher Lasch (while recognizing my ability, disparaged the topic) and Robert Wiebe (an historian of American democracy, gave me great support). I soon connected with two senior women doing women’s history, Anne Firor Scott and Gerda Lerner, and with about a dozen other young scholars, all graduate students, following their women’s liberation inclinations into history.

All of that said I want to comment on the phrasing of your question. Feminism was an entirely political movement then. Those of us in gradate school who began raising these issues in fields (history, anthropology, literature, etc.) did not think of ourselves as entering or even pioneering an academic field but rather producing serious intellectual resources for our movement. At the time, it hardly seemed like a smart academic move: there were no positions, no recognition from our profession. When it came time to get jobs, those of us who found them did so because women students pressed their colleges and universities for a different kind of education and some of those institutions–mostly public ones–reluctantly gave in. That’s how I got my first job at the State University of New York at Buffalo, as part of one of two or three women’s studies programs in the country.

So many prominent voices in the women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s – from Betty Friedan and Susan Brownmiller to Bella Abzug and Ruth Bader Ginsburg – were Jewish. Can you tell us about the role of Jewish women in the suffrage movement of the 19th century and the broader history of political feminism?

This is a very interesting question for exactly the reason you note: suffragists in most of the first wave, certainly its 19th century years, were overwhelmingly Protestant, as was the country. The one really important Jewish-born woman of note in the early years, about whom I have written, was Ernestine Rose, born Esther Potowski in Russian Poland in 1810. After a rebellion from her rabbi father, she moved to London, where she married William Rose and became a socialist feminist. The couple moved to New York in 1836, where now Ernestine Rose became the leading woman in the campaign to grant married women basic economic rights in the State of New York. From this position, she became a major influence on Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Rose considered herself a “freethinker” but she was definitely not a Protestant and her attitudes remained influenced by her Jewish background: Talmudic approach to texts, not approaching marriage as a divine sacrament…

In the first two decades of the 20th century, the suffrage movement was infused with immigrant working-class women, in which Jewish women were very prominent. Their numbers–pouring into parades and suffrage organizations–were in the tens of thousands. The two most prominent Jewish immigrant suffrage leaders were Rose Schneiderman and Clara Lemlich. Both were heroines of the Triangle Shirt Waist strike [Uprising of the 20,000] and fire [LINK: https://trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu]. Lemlich became a communist, Schneiderman a Roosevelt Democrat. They both linked suffrage to the legislative and economic concerns of wage-earning women. And I will add here that when we turn to the European suffrage movements, Jewish women – in the Netherlands, Hungary, Germany and even France and Italy – were very important.

I should add that there was considerable anti-Semitic sentiment among Protestant suffrage leaders. Stanton focused on the Jewish (“Old”) Testament attitude to women; Carrie Chapman Catt on the strange, “un-American” practices and behavior of immigrant Jews in her home state of New York.

Why were Jewish women so very numerous and influential in the second wave? One answer no doubt is the involvement of 2nd generation American Jews, their social justice concerns intensified by the Holocaust, in the civil rights movement….

Do you think your Jewish identity informs your work?

As I suggested about my generation of 1970s feminists, I would say my social justice commitments, my experience in the civil rights movement, my sensitivity as a Jew to discriminatory attitudes, my family’s emphasis on higher education and professional (as opposed to business) careers, and the strength of my Jewish women ancestors, my mother and grandmother, working women both.

One of the significant contributions of your first project after coming to UCLA – Unequal Sisters: A Multicultural Reader in U.S. Women’s History – was to move our understanding of the suffrage movement beyond its traditional focus on middle-class and elite white, Protestant women. How will your new book expand our understanding of the suffrage movement?

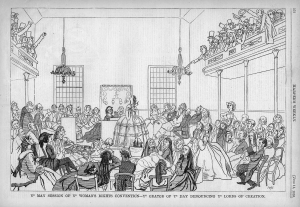

The new book – Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote – is the first comprehensive, evidence-based history of the American suffrage movement to appear since 1959. That book [Century of Struggle] was written by Eleanor Flexner, the daughter of an assimilated Jewish family in Louisville, Kentucky. Since Flexner wrote her superb book–on which I and virtually every other suffrage historian has relied–there has been tremendous amounts of new research that has enhanced our picture of the suffrage movement, or I might say, suffrage movements, particularly on the activism of African-American women, who were segregated out of the white-dominated movement in the late 19th and early 20th century. Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote aims to encompass this new research, and is also the first time I have written a book especially for a trade publisher and a general audience. I hope your readers will like it!

The new book – Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote – is the first comprehensive, evidence-based history of the American suffrage movement to appear since 1959. That book [Century of Struggle] was written by Eleanor Flexner, the daughter of an assimilated Jewish family in Louisville, Kentucky. Since Flexner wrote her superb book–on which I and virtually every other suffrage historian has relied–there has been tremendous amounts of new research that has enhanced our picture of the suffrage movement, or I might say, suffrage movements, particularly on the activism of African-American women, who were segregated out of the white-dominated movement in the late 19th and early 20th century. Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote aims to encompass this new research, and is also the first time I have written a book especially for a trade publisher and a general audience. I hope your readers will like it!

Prof. DuBois’ book, Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote, is available for pre-order now.