1. Was there a single experience or discovery that launched you on the journey to explore Jews’ role in popular, North African music of the 20th century?

Absolutely. In 2009, I was visiting Casablanca and happened upon one of the last record stores in the cultural capital still in existence. Knowing little about Moroccan music at the time, I asked the proprietor to give me a “tour” of his remaining stock. He proceeded to select a number of LPs and 45 rpm records, place them on aging but high fidelity equipment, and then set the needle down––filling the space with some of the most incredible voices I had ever heard. He then let me know after nearly every spin that many of the artists we had just listened to were Jewish. Thus a journey began.

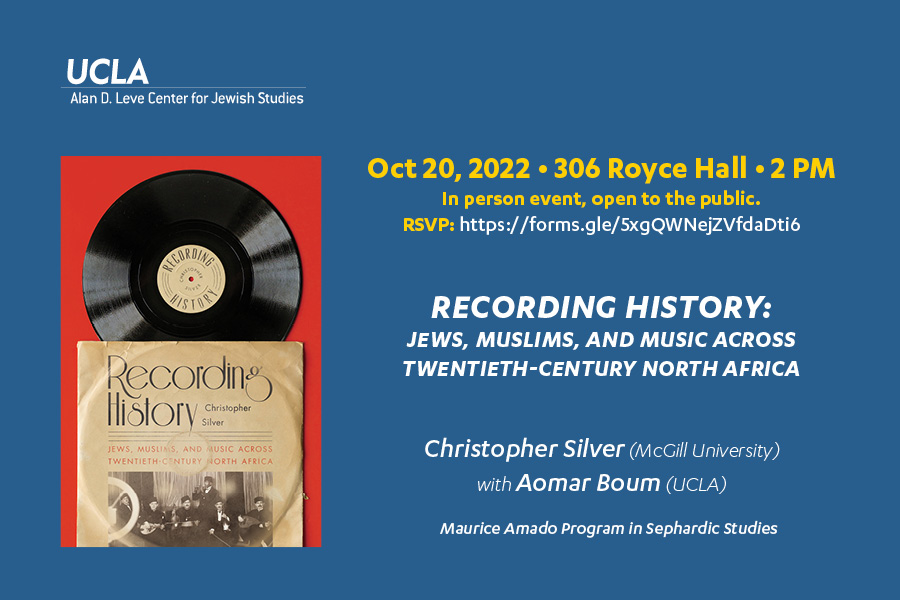

2. What story do you tell, in Recording History, about the relationship between Jews and Muslims in the music scene of modern Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia?

Of the many stories I tell in Recording History, perhaps the most resonant one is that history sounds different when we listen for it. The book charts the rise and cultural impact of Jewish music-makers and music-purveyors as sonic nation-builders and taste-makers at moments of monumental change across North Africa. That the Jewish minority helped provide the soundtrack for the Muslim majority is worth reflecting upon. So too is the fact that this phenomenon persisted for generations, including in the midst of decolonization. Through their popular sounds, for example, Moroccan, Algerian, and Tunisian Jews inculcated new ideas about what it meant to be modern—in Arabic. Their nationalist anthems raised up anticolonial movements both before the Second World War and after. The traditional story of Jews and Muslims in North Africa is one of separation and rupture, especially as the twentieth century roared on. This is a history of an enduring relationship well past points commonly presumed.

3. What was the most surprising thing you learned/discovered while researching and writing Recording History?

That so many records—in some case, more than a century-old—survived served as constant reminder of the importance of music to our historical actors. These discs are brittle, fragile, and heavy. Their contents stretch to no more than three minutes per side. Most people no longer possess the necessary playback equipment. Yet, individuals held on to them and carried them great distances in the midst of war, turmoil, and dislocation. Every time I hear the historical sounds embedded in their grooves, I am reminded why they did so and am rendered forever thankful.

4. Do you have thoughts about a future project that you care to share with us?

I am working on a few projects but one of them carries the story I tell in Recording History forward into the twentieth and twenty first centuries but with a focus on cities like Jaffa, Marseilles, and Montreal. My research will ask new questions about migration, diaspora, and contested identity through a focus on music. Once again, it will compel me to seek out different types of archives, including record stores, which, of course, sounds more than fine by me.