Catherine Bonesho joined UCLA in 2018 as an Assistant Professor in Early Judaism in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. She came to Los Angeles after a year as a fellow at the American Academy in Rome and received her PhD in Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Prof. Bonesho’s research aims to locate the history, languages, literature, and culture of Judaism in the Second Temple and Rabbinic period in their imperial contexts. She is interested in the ways that ancient Jewish communities navigated living under imperial domination through the development of legislation and rhetoric about the Other, and is currently working on her first monograph exploring the polemic of holidays and festivals to demarcate identity in early Jewish literature. She has also written extensively about language and translation, particularly the use of Aramaic in Greek and Roman antiquity, and during her time at UW, was one of the developers of the Wisconsin Palmyrene Aramiac Inscription Project.

Catherine Bonesho joined UCLA in 2018 as an Assistant Professor in Early Judaism in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures. She came to Los Angeles after a year as a fellow at the American Academy in Rome and received her PhD in Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Prof. Bonesho’s research aims to locate the history, languages, literature, and culture of Judaism in the Second Temple and Rabbinic period in their imperial contexts. She is interested in the ways that ancient Jewish communities navigated living under imperial domination through the development of legislation and rhetoric about the Other, and is currently working on her first monograph exploring the polemic of holidays and festivals to demarcate identity in early Jewish literature. She has also written extensively about language and translation, particularly the use of Aramaic in Greek and Roman antiquity, and during her time at UW, was one of the developers of the Wisconsin Palmyrene Aramiac Inscription Project.

We connected with Prof. Bonesho this week to discuss her work, her teaching, and how she’s working to expand our understanding of the Ancient world in the 21st century, digital reality.

Tell us about how you found your way to Jewish Studies. What inspired your interest in the intersection of ancient Judaism and empire in the Near East?

I stumbled upon Jewish Studies because of my love of languages. While pursuing my undergraduate degrees in Biology and Classics, I wanted to take another ancient language and ancient Hebrew just happened to fit into my course schedule. After reading through portions of the Mishnah, the Hebrew Bible, and some manuscripts of the dead sea scrolls, I was hooked. After working in a biology lab for a couple years, I realized that reading ancient Jewish literature was my true passion and decided to go back to graduate school. My specific interest in Judaism and empire comes from my study of the Roman Empire and the Latin language. I kept wanting to bridge Jewish Studies and Classics in order to better elucidate what it meant for ancient Jewish communities to live under Roman rule, and I continue to do that work here at UCLA.

You’ve worked not just on ancient Jewish languages, but also the material culture surrounding those languages. How does that work connect to your interest in empire? How do you understand the connections between language, texts, and imperial domination?

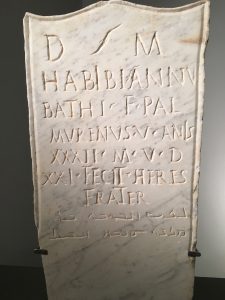

One of my specialties is the ancient language of Aramaic and its various dialects. Ancient Jewish communities, as well as other communities, such as the citizens of the city of Palmyra, continued to use Aramaic even after the arrival of the Greeks and Romans in the ancient Near East. In recent studies on Palmyrene Aramaic, I have analyzed how ancient Palmyrenes displayed Aramaic with respect to the prominent language of the Roman Empire of Latin. I found that Palmyrenes consistently displayed Latin in a more prominent manner than Aramaic (either as a larger text or placed above). This display highlights the effect of empire. While Palmyrenes in some way incorporate Roman rule by fronting a Latin text, they still subtly subvert Roman rule by continuing to include their native Aramaic language. The material presentation of these languages thus showcases a complicated identity for Aramaic speaking populations that simultaneously accommodates and resists Roman imperialism.

You’ve got a new article coming out – tell us about it and how it fits into your book project?

I have an article forthcoming with the Journal for the Study of Judaism that is related to my first monograph on gentile festivals in ancient Judaism. In the article, I examine Jewish literary descriptions of the gentile celebrations of the festival of Dionysus and Saturnalia found in 2 Maccabees and the Palestinian Talmud, respectively. The Jewish authors of these texts describe the festivals in ways that showcase their specific problems with Greek and Roman rule. For example, in 2 Maccabees’ description of the festival of Dionysus, the authors emphasize how the festival and other Greek customs may conflict with the proper observance of torah. Gentile festivals thus act as a significant means for ancient Jewish communities to respond to Greek and Roman hegemony, and reifies how they define their own Jewishness.

The questions you are interested in seem so relevant to other periods/epochs of Jewish history. Is that the kind of comparative work you’re doing in your Jewish Studies 10 course? Can you tell us about how you’ve refashioned the course?

Definitely, my work on Jewish communities in the ancient Near East showcases how diverse communities define themselves under different circumstances. I take a similar approach in the Introduction to Judaism course that I offer every fall. The course surveys a variety of Jewish communities throughout both time and space, including the communities of the Hebrew Bible, the classical rabbis, the Karaites, and modern Jewish movements in the United States. Throughout this survey, I ask students a seemingly simple question: what is Judaism? Turns out answering this question is not so simple. I prepare students to answer this question by having them engage with a range of primary sources and topics. In the process, students explore how Jewish identity, textual traditions, and religious practices combine to define “Judaism” differently in diverse times and places.

I think a lot of people might assume that digital tools would be anathema to the methodologies that you and other scholars employ to understand the Ancient world, and yet you’ve been working in the digital sphere for a while. Can you tell us about the Wisconsin Palmyrene Aramaic Inscription Project and how you’ve been doing paleography digitally?

While at the University of Wisconsin, I co-founded the Wisconsin Palmyrene Aramaic Inscription Project (WPAIP), whose goal is to collate and digitize Palmyrene Aramaic inscriptions, which are texts physically inscribed on materials like limestone. This group has collated a variety of inscriptions found throughout the United States via a specialized form of photography that better illuminates the contours of ancient inscriptions. I continue to work on the digitization of Aramaic inscriptions and am currently developing a new digital humanities project on Aramaic throughout the Mediterranean that continues the rich history of Aramaic Studies here at UCLA.